Part II.: The Changing Landscape of Audio Technology 1969-1994

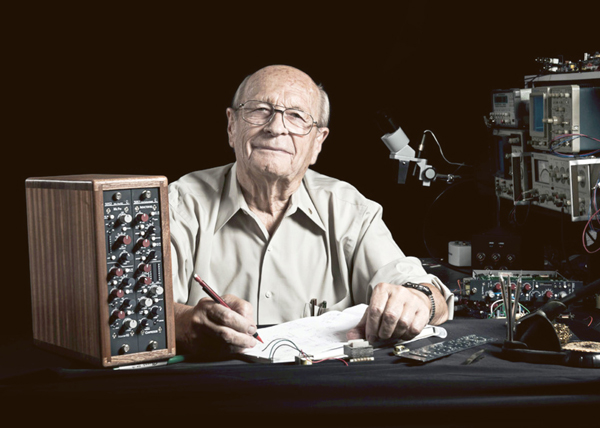

February 2021 was a cruel month for so many of us and for recording engineers it brought the added grief of the passing of Rupert Neve. Few have done more to advance the art and craft of recording technology, providing generations of engineers with the tools to create the most extraordinary recorded music.

He designed his first consoles with solid state electronics in 1964, and by 1970 the success of his company was assured with production moving out of the Little Shelford home facility into a purpose-built factory. Demand grew rapidly with record companies recognizing the unique quality of his equalizers and the sonic clarity of his designs. From 1969 to 1973 Mr. Neve designed a series of legendary modules with numbers that still resonate 50 years later: 1064, 1066, 1081, 2254 and perhaps the crown jewel, the 1073. Neve consoles, notably the “80-series” achieved phenomenal success in the mid-1970s as leading producers and engineers from around the world came to view Neve products as indispensable tools.

Working closely with producers and engineers such as George Martin and Geoff Emerick, Mr. Neve came to understand that our ears and minds could perceive so many things that could not easily be described with simple traditional measurements but which, when present, added life, fullness, and emotional appeal to recorded sounds and music.

Despite the overwhelming praise for Neve designs in the 1970s, many designers of audio equipment failed to appreciate exactly why these products sounded so wonderful and for several decades they continued to both accept and promulgate time-honored ideas about the limits of human auditory perception which Rupert Neve and others had discarded by the 1980s.

The Neve company became a publicly traded enterprise in 1975, and during the second half of a ten year non-compete agreement Mr. Neve (doing business as ARN Consultants) was largely occupied with a variety of audio projects not related to the design of large mixing consoles. Meanwhile, the entire music and recording landscape was undergoing a dramatic change in the 1980s and many of the cherished products from the 1970s seemed to fall by the wayside, along with the advanced notions of human perception which had guided their development to a very advanced state by 1978.

The late 1980s saw professional audio rushing towards its digital future. Affordable digital recording had arrived with the R-DAT compact digital cassette in 1987 and CDs had become the dominant media for music distribution by 1988. The early 1990s promised a fully digital production chain. Digidesign’s Sound Tools (1989), Pro Tools (1991) and the Alesis ADAT (1992) were just a few of the innovative products that would spark an explosion of project studios with capabilities that rivaled the midsize professional studios of the previous decade

With those dramatic changes on the horizon, many saw vacuum tubes, transformers, turntables and vinyl records as audio dinosaurs on the road to extinction. Interest in vintage gear was minimal. How shocked a young engineer from the 80s would be if they were suddenly transported to our world where so many of these “dinosaurs” have revived and are cherished by professionals and consumers alike.

What happened along the way is that many began to realize that the new technologies all too often did not quite deliver the superlative audio that digital promised. “Perfect Sound Forever” didn’t quite pan out. So even as the digital tide rolled in, a good number of engineers realized that there were so many aspects of the audio quality that were not clearly understood and which often could not be easily measured. As these came to better appreciated in the 1990s, there was a simultaneous re-evaluation of older technologies and vintage equipment. Today we better understand what a magnificent and complex auditory mechanism humans are blessed with and how the most subtle factors can be perceived and influence what we call “good” sound.

In 1985, Mr. Neve’s non-compete came to an end and at the same time the Neve Group was sold to the Siemens corporation of Austria. Rupert and Evelyn Neve then re-entered commercial studio supply, launching a new range of outboard equipment under the name of Focusrite Ltd. Of course, loyal Neve followers wanted nothing less than his return to the business of creating large format mixing consoles. Orders were taken for 8 new consoles with new and complex digital master control facilities. Sadly, the task exceeded the company’s resources. Both time and money ran out and the company was liquidated in early 1989.

Despite this disappointment, Rupert Neve was once more about to re-shape the way many thought about audio and equipment design. Entering into a consulting agreement with the English console manufacturer AMEK, Mr. Neve immediately began to design upgraded modules for some of AMEK’s most successful products, along with a new outboard equalizer. By 1993 a full range of new outboard gear was launched – the 9098 series – which would culminate in his new Super Analogue console by the decade’s end. AMEK provided Mr. Neve with a unique opportunity to reach out to the international audio community through both print advertisements and in-person appearances which highlighted the design principles that were so central to the success of his products.

AMEK was not shy about their “re-introduction” of Mr. Rupert Neve. One advertisement boldly stated:

“Perfection remains a dream… One man has made it his life’s work to pursue this dream and more than most, he has come close to making it a reality. Time after time he has challenged the conventions and rewritten the rules. His hallmarks are an unwavering commitment to the detail of circuitry design and a lifelong dedication to improvement. His signature is a guarantee of audio excellence. Many people point to his history. Only AMEK can bring you his future.”

Though in many ways Mr. Neve shunned the spotlight, he did allow AMEK to include his picture and to quote him liberally in advertisements that proclaimed an expansive concept of auditory perception:

“For more than a decade leading musicians and engineers have appreciated that exceptionally wide bandwidths with very low distortion are vitally necessary in the early stages of the signal handling chain. Now academic research has endorsed our experience, finding evidence that signals as high as 100 kHz are used by the brain to add fullness and enjoyment to music… owners can rest assured that these performance parameters are an essential part of my decisions.”

Responding to criticism of these statements in 1992, Mr. Neve added:

“We try not to stand still and as we learn more and continue to listen to the musician and producers, so we will build the sort of equipment that we think adds fullness and enjoyment to music even if we do not fully understand all the factors that make it so. We cannot ‘explain’ how we respond to sounds. There are many researchers who have made and are currently making extremely valuable contributions…”

Mr. Neve then cited four papers presented at Audio Engineering Society conventions and meetings in 1991:

“High-frequency sound above the audible range affects brain electric activity and sound perception” (Institute of Multi-media Education, Japan)

“Estimating the Significance of Errors In Audio Systems” and “Predicting the Audibility, Delectability and Loudness errors in Audio Systems” (J. Robert Stuart, Boothroyd Stuart Ltd, U.K)

“Understanding Noise and Distortion- A New Approach” (J. Robert Stuart, Boothroyd Stuart Ltd, U.K)

Mr. Neve had begun to test his ideas with public experiments in 1987 and once the AMEK consultancy was in place, he expanded these tests to include audiences in several countries. The audiences were always professional audio people, musicians and engineers and producers who are used to critical listening. A notable US demonstration took place in the fall of 1990 at U Mass Lowell, where the Music Department’s William Moylan, a highly regarded author on sound recording technology and music theory, had established one of first Critical Listening courses.

The repeated conclusion from these experiments was that although traditional measurements limited human hearing to an audio bandwidth of 20 Hz to 20 kHz, human perception can be aware of frequencies that are well above this and that when these frequencies are eliminated from the audio chain during the recording process, the results are a loss of quality in music reproduction and a perceptible reduction in listener enjoyment. While many subjects were discussed in Mr. Neve’s extensive talks to audio engineering professionals and students after 1989, this concept of wideband high fidelity was to be an essential component in all his lectures.

During those critical years beginning in 1990, Rupert Neve was instrumental in getting engineers to re-think their long-held views about the limitations of human hearing. Along with others, he led a movement over the next twenty years to examine the subtleties of perception and to create audio equipment that not only performed well on paper but which also transmitted that hard-to-define magic that we experience directly with a live performance or by way of a superbly recorded mix.

When he reclaimed full use of his name and launched Rupert Neve Designs in 2005, his newest designs received immediate acclaim and achieved astounding success. While some would continue to argue against his ideas regarding how we perceive sound, few could question that once again his designs had given audio engineers the most extraordinary tools to elevate their craft to true art.

Josh Thomas, who had been working with Rupert Neve since their days with AMEK, summed up the twin goals of Rupert Neve Designs:

“The first was to set a new standard in the quality of recorded sound, drawing upon his unparalleled depth of experience to create high-end solutions for the modern recording engineer, musician, and listener alike. The second was to pass on his philosophies, techniques, and methodologies to a new generation of designers to carry his life’s work and passion into the future.”

The recording industry responded with unprecedented accolades including a Lifetime Achievement Technical GRAMMY Award in 1997, Studio Sound Magazine’s Audio Person of the Century Award in 1999, an Audio Engineering Society Fellowship Award in 2006, and 16 TEC (Technical Excellence and Creativity) Awards for Rupert Neve Designs.

In Part III of this essay, Rupert Neve and others challenge the 20-20K dogma, laying the foundation for a new and expanded definition of the boundaries of auditory perception.

Part III:

Can You “Hear” This?

Re-Examining the Limits of Auditory Perception

Beginning in the late 1950’s leading designers of consumer and professional audio equipment begin to search for a better understanding of the factors that influence the “sound” of their products and the way that listeners respond to their sonic attributes.